Illusions behind glass

The screen has become omnipresent in our lives: starting with TVs entering our homes, then computer monitors, smartphones, tablets, VR sets. We’re all looking through glass walls at illusions.

The illusion is not confined to films, tv programs, and funny cat videos on YouTube, but also incorporates the way we use apps, the windows in our browser or text editing software, and the internet itself.

For instance, one of the largest sites – in terms of visitor traffic – is Wikipedia. Most people use only the top layer of this online encyclopedia, searching for information on a wide variety of topics. Many are aware of the fact that the site is maintained by a fluid community, which might include literally anyone. However, only a small number of people do contribute to the site, or know that often serious discussions take place before changes are made or a new page is set up. Wikipedia is extremely transparent about this: all the visitor has to do is hit the ‘talk’ button next to the top of the article.

This is layer two: the backstage of the published content, so to speak, opening up a whole new world of interactions. Here, we find ‘edit wars’, a whole range of abbreviations (WP:3D, WP:GF, WP:HA), absurd deviations – when editors are on a roll -, conspiracy theorists, fringe theories, crazy questions, arrogance, and added knowledge.

A nice example of a typical runaway discussion is this thread concerning the exact angle Duchamp’s fountain was rotated in order to make it an artwork instead of a useful urinal.

Digging deeper will get the visitor to guidelines, Wikipedia humor, games, pages that are up for deletion, or insolvable disputes and blockades. Somewhere in between move ‘bots’, crawling the site for lost links, or vandalism – these small programs are written by members of the community, and hover on the verge of the backstage and the mechanisms of the website itself.

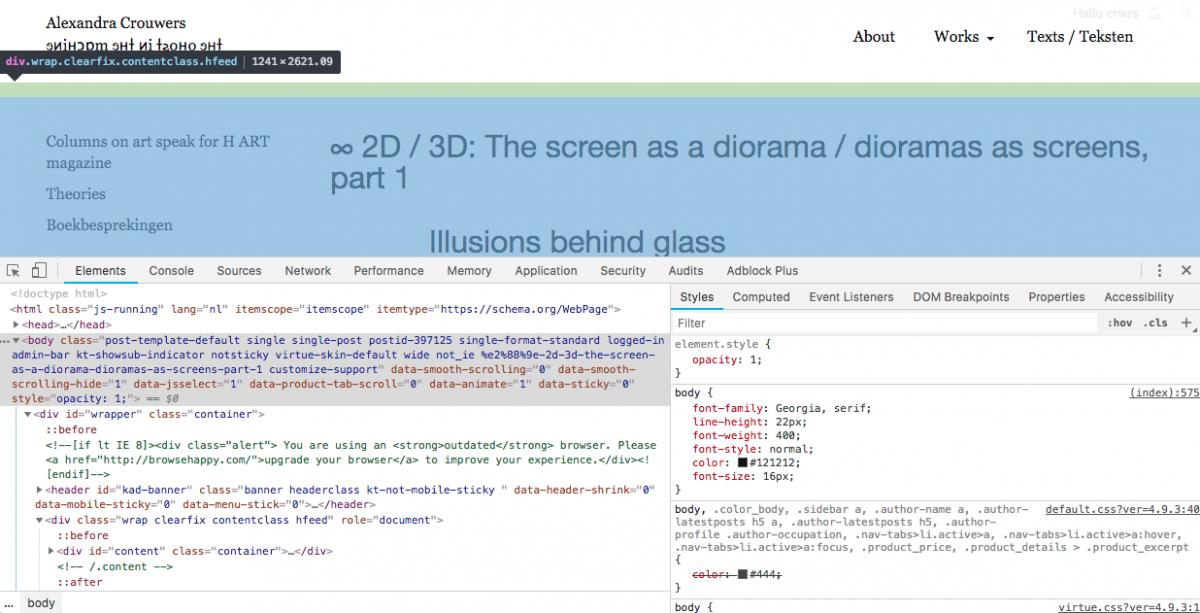

Technical layers such as CSS – the language that defines a website’s design – and html code – which is responsible for hyperlinks and a website’s structure – are even further down, on top of the internet protocols themselves, which are in their turn part of the World Wide Web that now defines the internet.

This is very much an architecture, all made available through a flat screen. I’m proposing the screen as a diorama.

Dioramas

When I first arrived in New York in 1974, I visited many of the city’s tourist sites, one of which was the the American Museum of Natural History. I made a curious discovery while looking at the exhibition of animal dioramas: the stuffed animals positioned before painted backdrops looked utterly fake, yet by taking a quick peek with one eye closed, all perspective vanished,and suddenly they looked very real. I had found a way to see the world as a camera does. However fake the subject, once photographed, it’s as good as real. – Hiroshi Sugimoto

There are various definitions of a ‘diorama’. According the aforementioned Wikipedia a diorama “can either refer to a 19th-century mobile theatre device, or, in modern usage, a three-dimensional full-size or miniature model, sometimes enclosed in a glass showcase for a museum.” Although both the theatre devices and the miniature models are interesting in their own right, I would like to focus on the full-size diorama, enclosed in a glass showcase.

The glass is important, because it prevents the onlooker from interfering with the scene. The most common diorama in that sense is the natural history diorama: the simulation of a scene from reality, reconstructed from a blend of real and artificial 3D and 2D components. It’s a frozen set, creating the illusion of it being a window to the world of a certain animal: it’s a spatial snapshot. This artificiality is in great contrast to the natural situation it depicts. Because of that, to me, a diorama is ‘moving’ in the emotional sense.

Some dioramas are literary moving. They might have day/night cycles with colour-changing lights or mechanical movement built into the models. I’ll come back to that later.

Since artificial intelligence has no idea of what we experience as reality, Machine Learning is based on understanding reality only from the various representations of reality that are being put on its plate: photographs, film, text.

Back to the screen.

The computer screen is similar to the glass front of a diorama. More so when working with 3D software, which enables me to build my own dioramas, to carefully construct a simulation of an ‘unreality’. It’s world building.

Here’s also a big difference between the (computer) screen and a diorama: large portions of the scenes behind the screen glass are interactive, meaning the viewer is able to interfere with the scene. Hypertext and links function as zappers or portals. Games provide the experience of an avatar moving around the supposed diorama.

AR

Reversely, the classic natural history diorama is very much a screen. It’s well lit. The space a diorama is set in is much darker, even in nocturnal animal scenes. A diorama has real depth, as opposed to the digital/virtual depth of a screen. But still, it’s impossible to walk through it, or to view it from another side. The set is carefully composed towards you, the viewer. It’s not entirely flat either. A diorama is more like a stereo image: the illusion of depth in a flat surface, with a limited 3D view.

Virtual Reality has been in the 3D picture for a while now, but it still requires some bulky headgear and a hoopla of technicalities. Augmented Reality might become much bigger: the tablet or phone screen is used as magic glasses, transforming the world in front of you as long as you keep looking at the screen. The illusion is the screen itself: it tricks you into the feeling of looking through it, but you’re in fact simply looking at it while it displays what the camera sees. At some point the device will probably be made entirely from glass, so you would actually see through it.

See also this article on The Verge from 2013 (!)

The first ever example of AR I saw years ago at the Museum of Natural History in Berlin, where dinosaur skeletons turned into animals of flesh and blood when looking through a special viewer.

At the moment, my phone is still a bit too old for augmented reality apps, but it could be interesting to try something out, similar to www.poeziemuseum.amsterdam, an app that simulated pavilions with poetry on the Amsterdam museum square, between the Rijksmuseum and the Stedelijk Museum. Pretty nifty.

So far, part one.