Bits & Pieces

Publications for Belgian art magazine HART (now GLEAN). WAGMI: an awkward dance of art and crytpo is an article on the NFT phenomenon (published in HART magazine #222, March 2022). Bits & Pieces are four short columns on digital art pieces from my NFT collection, published online on the magazine’s website. Dutch and English.

WAGMI: an awkward dance of art and crypto

As it turns out, much of the turmoil surrounding the NFT—the non-fungible token, often erroneously dubbed crypto-art—arises from a wide range of misunderstandings. Since Spring 2021, I’ve actively been exploring the phenomenon from the perspective of my professional artistic digital practice, which took off in 1998 with a discarded office computer and CorelDraw. This resulted not only in an explosive network expansion but also in a growing digital art collection. As with all things, this virtual field is endlessly more nuanced than it may appear from the outside.

* WAGMI: We’re All Gonna Make It

An NFT is not a new medium posing an existential threat to painting or sculpting but simply a way to distribute digital files with a certificate of authenticity by its creator, immutably and publicly recorded on a blockchain. The file can be anything from a screenshot of a Tweet to a snippet of code or a rental agreement. But it can also be a purchase contract for art. Cryptocurrencies, too, are connected to blockchains and are equally elusive and immaterial in nature as digital art. Apart from these substantive similarities, crypto-investors often deploy pump and dump tactics that are reflected in some areas of the physical art market, despite its aura of civilized decency. And this is how an explorative segment of the visual arts has gotten itself into an awkward and sometimes overly excited dance with crypto.

Much of truly digital art has barely any means of existence outside of the realm where it was produced. You can’t print a .gif animation, and it’s impossible to touch an augmented reality piece. Code doesn’t manifest itself in real world coordinates. These works live where they were born: in strings of zeros and ones, visible on the screens of (mobile) devices.

For artists like me, whose process and production largely take place in—and relate to—a virtual environment, the NFT provides at least a partial solution to a problem. NFTs allows me to distribute—and yes, also monetize—works that had trouble finding a logical destination before. By applying my ‘stamp’ of authenticity, I’m telling everyone this file is made and provided by me. The stamp manifests itself as metadata and is comparable to, for instance, a signed and numbered silkscreen edition.

But what about that exorbitantly high energy consumption that has become synonymous with crypto? Well, my work centers on ecological collapse and the planetary climate crisis; there was no way I would have, or could have, engaged with the NFT space if not for alternative blockchains such as Tezos, where a transaction uses less energy than sending a Tweet. And since I’m not alone in this, within less than a year, a dynamical ecosystem arose from thousands of artists, developers and collectors moving between platforms such as versum.xyz, teia.art, and objkt.com. This part of crypto space behaves like a global artist-run space, and is quite different from the, still to me too, peculiar trade in pfp projects so often associated with NFTs.

This brings me to my collection. Almost every earning from the sales of my own works—which I offer for quite democratic prices, since I’m considering this space as a fascinating experiment in progress—flows back into the ecosystem via my purchases of works by colleagues from all over the world. This includes work by monuments of digital art but also by lesser known, anonymous or sometimes very young creators still trying to find out where they fit in or outside of the fine arts context.

It may be difficult to grasp for people less familiar with digital matter but the sense of ownership is surprisingly similar to owning a physical art piece. Like some sort of meta-archivist, the blockchain adds my name to a work the moment I acquire it. The NFT is the handshake between artist and collector, and establishes a bond between us. Confronted with increasingly overwhelming amounts of digital visuals, it can be hard to locate meaningful and interesting trajectories. A digital picture is not automatically ‘art’ and it takes some good old-fashioned knowledge of the new media landscape and wider art history to separate hollow promise from relevant, more layered practices.

Bits & Pieces: Cofveve.

.gif art by Lorna Mills

Lorna Mills. Cofveve.

Animated Gif, 700 x 700px, 10 frames, 10 fps, 2020

objkt/110635

In a fairly recent development, digital art can be traded and collected in editions through means of NFTs (*). Alexandra Crouwers is building a collection based on her own digital artistic practice. The collected works are by established names, but also by anonymous creators. In step with the paper issues of HART magazine, this online section highlights one work from this collection.

No one really knows how to pronounce ‘gif’ in English. In Dutch, ‘gif’ is actually a word meaning ‘poison’. That’s why there is only one realistic pronunciation in the Dutch language area, using a peculiar pronunciation of the ‘g’ that seems to be unique to that language. English speakers have several options to choose from in this area. Tomato, tomato, right?

The pronunciation of ‘cofveve’ is less important than its possible meaning. This particular and unlikely combination of letters stumbled into history through a tweet by Donald Trump. On 31 May 2017, at six minutes past midnight, the then President of the United States of America posted: “Despite the constant negative press, covfefe”.

Lorna Mills is a monument to .gif art and a connoisseur of the inappropriate. Mills descends into the catacombs of the Internet only to emerge with disturbing, comical, creepy and slightly offensive artefacts in the form of crudely edited .gif animations. She describes the angular, pulsating rhythm of the .gif as human vital signs, like heartbeat and breathing.

Her .gifs are usually presented in museum settings as large projected collages, showing dozens of animations at once, next to and on top of each other, in a fragmented state of overdrive. Meanwhile, the individual components lead their own lives. Isolated from the low-quality home videos in which Mills found them, it can easily take more than two hundred views before the scene begins to make at least some sense.

In Mills’ gifomatic universe, however, you don’t always want to know exactly what you’re looking at. The piece pictured is relatively harmless, despite the exploding balloon cofveve (…)

* Non-fungible tokens are crypto-sales contracts recorded on blockchains – in this case, the energy-efficient Tezos – connected to digital files.

Bits & Pieces: HOW TO BURN A CRYPTOPUNK AND NOT FEEL A THING…….A TUTORIAL

Trash art by ROBNESS

Still from ROBNESS_V2, HOW TO BURN A CRYPTOPUNK AND NOT FEEL A THING…….A TUTORIAL, 2021, mp4, 1’02”, teia.art/objkt/168685

In 1966, the now legendary Destruction In Art Symposium (DIAS) took place in London. The event was centred on destruction as a performative act and featured, amongst many others, Yoko Ono’s famous Cut Piece, where the audience was ‘invited’ – with the aid of a pair of scissors – to cut up and tear the artist’s clothing.

The following decade saw the hippies of the 1960s and their singular message of Peace and Love shoved aside for a much bleaker and more violent world view, reflected in the punk movement of the late 1970s. As is often the case with the arts, DIAS turned out to be miles ahead of the social curve, with figures such as Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren turning destroyed garments into fashion.

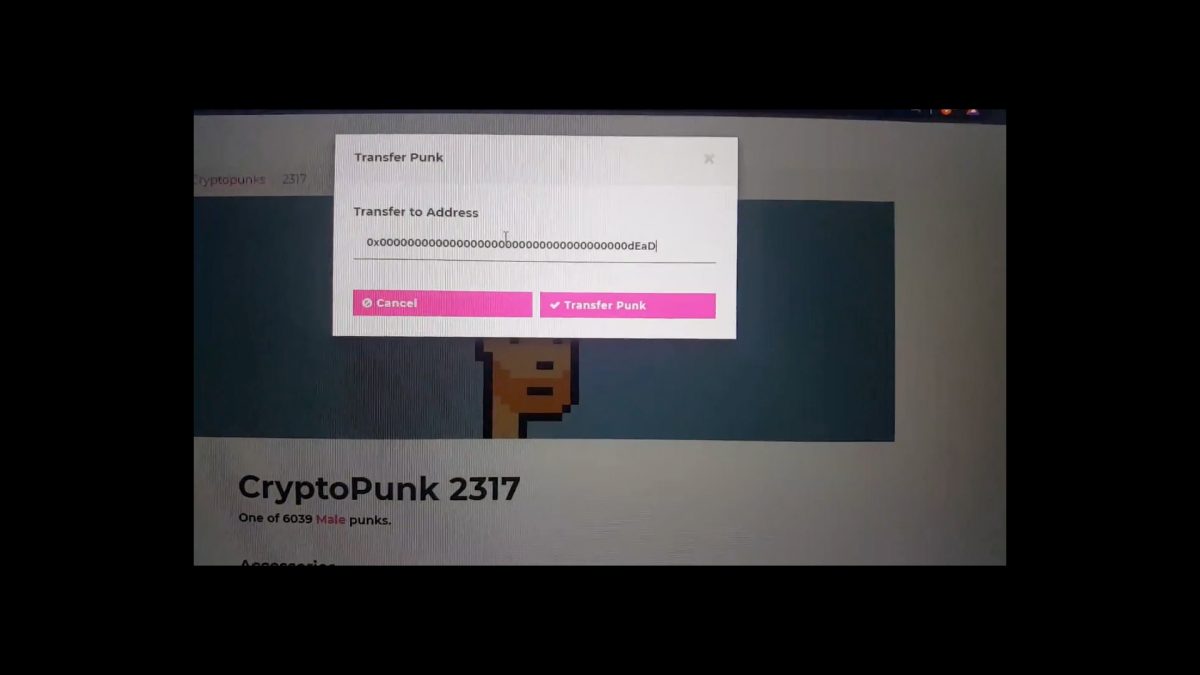

HOW TO BURN A CRYPTOPUNK AND NOT FEEL A THING…….A TUTORIAL(**) is a performance by Robness consisting of a video recording of the artist ‘BURNING A CRYPTOPUNK LIVE ON CAMERA’. His communication is characterized by a typographic holler: it’s ALL CAPS all around. It signals the authority of this crypto-art OG and king of the trash art genre [1].

With a swagger seemingly inherent to the West Coast of the US, Robness – present as a (to my European ears) eerily Elvis Presley-esque voice-over – films the computer screen using presumably his phone. He takes us through trashing an NFT. There’s such a wealth of art and crypto references to unpack here, my first draft for this column threatened to expand into a lengthy essay.

For the sake of this format, however, I’m resorting to compressing some of the associations I have with this work into a few sentences. First, there’s the anti-art movement in the tradition of Duchamp and Warhol. Then there’s the historical background of this particular NFT (a quintessential example of the commodification of an early anarchist PfP project [2]). The trash art/punk connection explores the idea of ownership and remixing in art, which reminds me of Pierre Huyghe and Philippe Parreno’s amazing project No Ghost Just a Shell (1999). And finally, inseparable from Robness’ own unconventional artistic trajectory, which got him temporarily banned from a large NFT platform, there’s the complex relation between libertarian blockchain pioneers, self-taught digital artists and traditional art world gatekeepers.

Obviously, the video-performance is a piece of NFT history for an number of reasons, but for a wider audience the most striking feature of the work is probably the fact that, at the time of writing this column, a CryptoPunk is worth the equivalent of about 160,000 euro.

Let’s return to what is happening on the screen(s). Robness enhances the casually brash atmosphere by first selecting James Brown’s The Boss as soundtrack, and proceeds to open a browser tab showing Punk 2317. He then pastes a string of letters and numbers into a popup field – this is a so-called ‘burn address’, the blockchain’s equivalent of a trash bin – and sends it off for processing: ‘Happy trash day, everyone.’

** OBJKT#166040 is the first part of the burning of Punk 2317, imagining the destruction of the image as a visual analogy.

*** In 1995, the K Foundation – former members of successful concept band The KLF – literally set fire to 1,000,000 pounds. They entertain a similarly frictional relationship with the contemporary art world.

[1] Trash art identifies itself with the use of ‘poor images’ or ‘lazy effects’. In the words of Robness: ‘I would joke, if you don’t make it in under 5 minutes, it’s not a Trash GIF.’

[2] PfP stands for profile picture, the avatar images used for social media instead of a portrait photo. Collections of generative images can be compared to wearing a personalized button of a favourite band, or to collectible cards. The artistic value is usually negligible.

Bits & Pieces: Ariel_Institute

AI art by ELLIE HEDDEN

Ariel_Institute, Suzanne_P1S1, Nico_P1S1, Trevor_P1S1, Gracen_P1S8, 2021-2022, png, 1001 x 1001px, edition of 1, www.teia.art/arielinstitute

In some parts of the world, children are not named until they reach a certain age. Once a chicken is named, it is transformed from a potentially juicy nugget into a pet. Names are an integral part of identity. My relationship to my machines is also expressed through naming: Leia II and III for the desktop computers, the older laptop is Han Solo III.

The cheerful young people in the works are part of a growing series of portraits, all published in batches of ten. So far, Nico, Lolimar, Gracen, Trevor, Scout, Suzanne, Jesalyn and Belinda have manifested. The images are ‘manifested’ because the people portrayed do not exist; they are synthetic faces constructed by machine learning.

A generative adversarial network (GAN) simulates neural learning processes in which software uses data sets – in this case tens of thousands of photos of faces – as a starting point for new computer-generated visuals. These synthetic images can sometimes be so convincing that they are indistinguishable from ‘real’ ones. There are already marketplaces where you can buy fake faces for commercial purposes. It’s convenient because synthetic people don’t need rights or ever complain.

The internet is full of fake identities. In some cases, only the user name of the creator is known, recalling the theatricality of performance pseudonyms such as Peaches, Lux Interior or Snoop Dogg. Fictional identities are the fog machines of our social media stages.

The Ariel_Institute (A.I.) produces a kind of test-tube character, emphasising the artificiality of the series in the descriptions of its activities (’transcription of perceptual kernels captured by A.I. protocol’) and in the project’s subtitles (‘Ariel Institute development protocol’). Fifth participant: NICO//: Phase.1State.1′) and in the frames surrounding the portraits, as if they were product labels.

The Institute is a project by Ellie Hedden – or Ellie Heden, depending on whether you visit her Twitter or Instagram account. But Ellie doesn’t exist either. Behind Ellie is an artist who makes beautiful videos about the fluidity of identity in almost mythological digital spaces. With some effort, a real name can be found, but for now it seems to be hiding in a growing crowd of fictitious faces.

Bits & Pieces: Open Life

Glitch art by Ina Vare

Ina Vare, Open Life. .gif, 2021, https://teia.art/objkt/345477

Jeffrey Sconce connects technology and the exploration of supernatural phenomena in his book Haunted Media. Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television (Duke University Press, 2000). Invisible forces of nature, such as static electricity or the disembodied voices travelling through the ether by means of radio-waves, are made detectable through equipment acting as mediums.

The portalesque qualities of machines and technology is a returning theme in the arts. The most well-known (and frightening) examples are probably the videotapes in Cronenberg’s Videodrome and Suzuki’s Ring. Director David Lynch uses audio- and video-glitches to signal the presence of another dimension. In the magnificent Twin Peaks: The Return, buzzing electric currents string the episodes together, suggesting each wall outlet as a possible means of transportation. In the Death Grips’ music video Guillotine (2011), the distorted music runs in tandem with glitched visuals.

Ever since The Matrix came out in 1999, the phrase ’There’s a glitch in the Matrix‘ has become commonplace. A ‘glitch’ is in fact a mistake, an accidental deformation. Where technology tries to achieve some sort of numerical perfection, the glitch sardonically screws the signal between the source and the output.

Everyone who has ever watched digital video knows the phenomenon: streaming disruptions inadvertently produce grotesque disfigurements and colourful disturbances. A bit further back in time, we have the static from worn VHS tapes, or the fuzzy ghosts of badly tuned tv stations. Lens flares – the light leak artefacts produced by aiming a lens directly into the sun – can be considered protoglitches.

In the technological arts, glitch art has become an important – and growing – subgenre, with Nam June Paik as its godfather. Superficially, glitch art is easily recognised by its rainbow-coloured statics – a characteristic of messing up the signals of analogue equipment – and loops, ultra-short scenes repeated ad infinitum.

It’s a remarkably ideological genre: glitch manifests itself by using equipment in ways it was never meant to be used. Software developers often have (glitch) artists test a new programme or feature by having them find ways to ‘break’ it. Glitching visuals are a metaphor for the perceived order in the world; the glitch leaves scratches in society’s glossy varnish.

This consciously celebrating of errors, and the purposely bending of conventions are central concepts in the psychedelic bodies of works of artists such as Sarah Zucker and Sky Goodman. The work highlighted in this column, Open Life, by Latvian artist and VJ Ina Vare is an analogue glitch portal in true form. As part of four other works (Open Portal, Open Soul, Open Gate, Open Space), it adds to an almost mystical quintet. And just like that, an accumulation of mechanical inflexions transforms into a visual meditation.